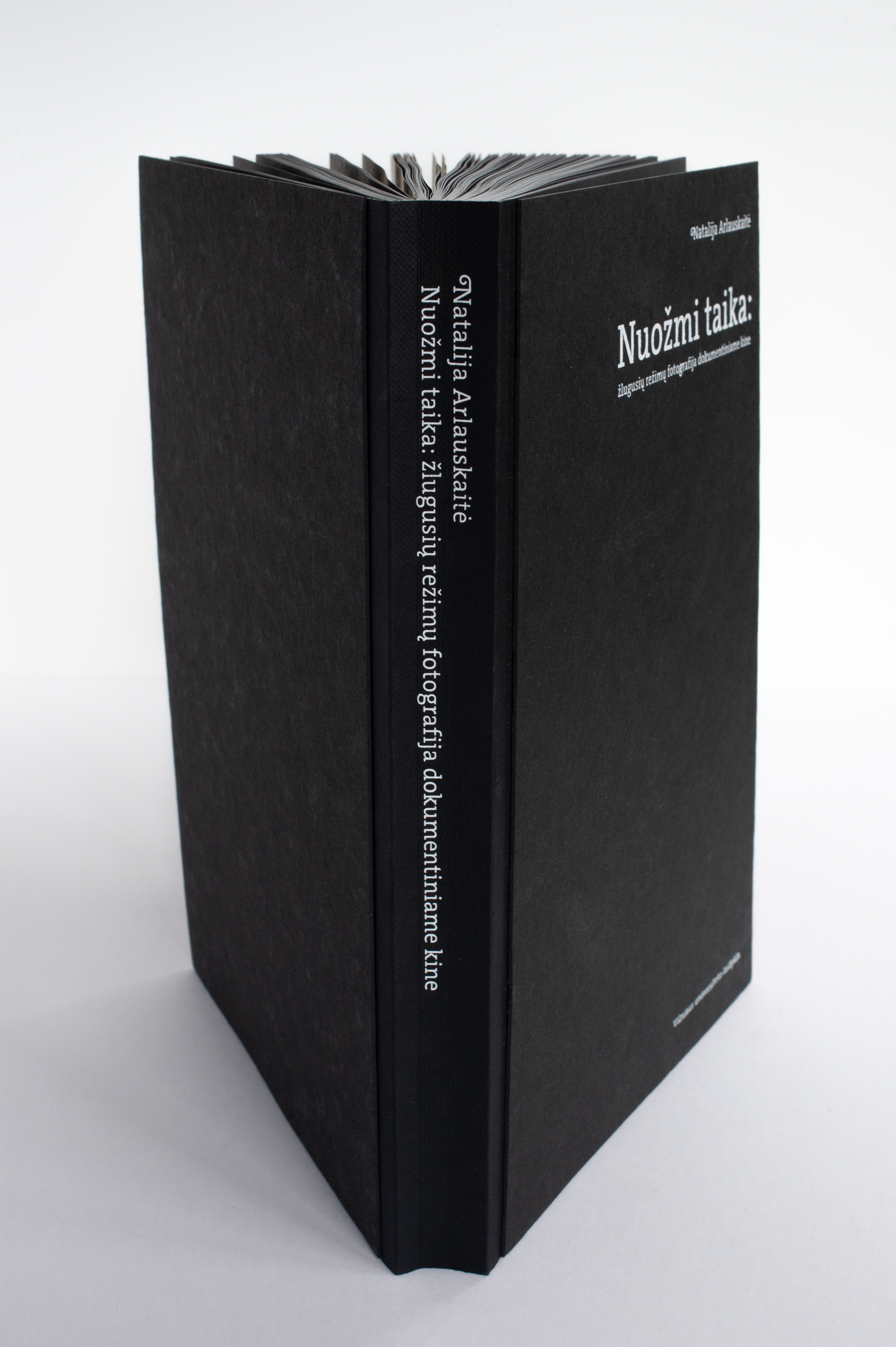

Original title: Nuožmi taika: žlugusių režimų fotografija dokumentiniame kine

Publishing date: 2020

Publisher: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla

Language: Lithuanian

Pages: 328

Description:

Archival documentaries, archival animation and archival projects of contemporary art analysed in this book remediate photographic archives of the collapsed regimes. In spite of the specific legal and political circumstances after ‘the fall’ in, for example, Cambodia and Portugal, the strategies of cinema and contemporary art to think through the photographic documents of the fallen regimes that have Lithuanian material at its centre share certain similarities that enable comparisons with strategies adopted in Russia, Poland, Estonia and Finland, that is, in a broader sense, in the world after the fall of the Berlin wall. Put another way, the films that are analysed here tell us about the relationship with the past that does not always subside into the self-evident; they tell stories which for a long time were impossible to tell, paying attention to visual documents that change the scale and the angle of history-telling.

The two types of photography – institutional and private – are discussed while developing broader analytical approach to visual regimes; it is an approach that connects political optics with the vision of reality. Photographs encountered in the files of repressive institutions are always related to the institutionalization of the state of subordination (criminal, political enemy) as well as citizenship suppression or other form of its regulation, where citizenship is understood as the degree of subjectivity in the state or government’s field of vision. In and of itself, the process of taking a photograph while registering, arresting and imprisoning works as the optical technology of citizenship. It is characteristic not only of totalitarian or authoritarian governments, but also, for example, of anthropological or demographic visions in imperial contexts, where citizens and the extent of citizenship or subjectivity are also assorted and catalogued. Remediation of the photographs both explicitly rejects the power of fallen regimes and establishes – even if temporarily and situationally – the possibility for a new or alternative citizenship, i.e. optical citizenship of a new order.

The ways of changing this order that are highlighted in the documentaries, documentary animation, art installations and museum projects analysed in this book are primarily related to the specificity of photography as static media. Taking a police photograph out of the repressive archive, in other words, its de- and re-archiving, sets that photograph in motion and changes its temporality. The static image in police photography gains duration either through the process of comprehension that requires the viewer’s bodily involvement (for example, by moving between photographs or by touching their contours, transposed onto another medium, as if developing negatives) or in the new order of cinematographic visuality, when, for instance, photographic image starts moving by invoking animation effects. In both cases, what happens is the deterritorialization, discursive dislocation and shift of photographic images. In archival documentaries, archival animation and some contemporary art works, visual deterritorialization is accompanied by vocal or acoustic deterritorialization, when both voice and sound strategies, responsible for the unity of or antagonism between knowledge and power, become the main grounds for establishing discursive shift and emancipated subjectivity. Thus, the politics of the voice in archival video, cinema and animation projects is essential for the analysis of change in visual as well as audiovisual regimes.

The relationship between private photography and the state is by no means as obvious. When placed in the narratives about regime change, such photographs fix the familial gaze, responsible for a conventionally ideal image of community, and open the national romance – an account that records family album into the national and state narrative at the same time as it records the nation and the state into the photographic image’s structure of meanings. Just as the police photographs, the accounts from the time of the two Soviet occupations, when told through archival documentary and animation, disarrange privacy, family and state through visual and vocal deterritorialization of the image, obtained by adjusting the temporality of that image. However, when family album’s photographs enter the junctions of cause and effect (however minimal they might be), it is not the duration effects that make them mark political breakthrough and optical and auditory change, but rather their anachronistic use (the multidirectional temporality of their remediation), which regulates the relationship between the knowledge that had been there at the time and the knowledge that was obtained much later. The rearrangement of family photographs intertwines with other state, institutional and private archives in these accounts, as they participate in discussions on Post-Soviet Post-colonialism and suggest not only quite clearly identifiable variations of occupational or colonial discourse but also their substantial revision.

The aforementioned revision occurs while reflecting on the templates that are available for narrating the (Soviet) past; it transforms the often-refutable magnitude and repertoire of those templates into its main object of enquiry. In this case, revision is understood in its literal sense as reviewing, repeated close observation or examination of vision. The reflexive character of revision enables us to compare the accounts of the Soviet era with those of the World War II; most of the material discussed in this book is in some way related to the latter. The concepts of secondary witnessing or postmemory, as developed in memory studies to mark the integrative character of the second generation’s accounts of the World War II and the Holocaust across different media, are built upon through the related concept of the third generation’s narratives. Reliant on photographic documents and told through archival documentaries and animation, third generation’s narratives are not exactly intended to fill in the lacunas in the visibility and in the circulation of images of the past, as the secondary witnessing of the second generation does. They rather perform the task of revision of the narrative and visual modes available, without making suggestions for identification with any of the narratives. In the context of the accounts about the Soviet era, this gesture offers an opportunity to answer the question: when does the Post-Soviet end? At the time when the third generation’s narratives emerge, even if they are not necessarily prominent.

Cite as: Arlauskaitė, N. (2020) Nuožmi taika: žlugusių režimų fotografija dokumentiniame kine. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla.

Purchase here.